Exhibition

Pioneer, genius: this small format exhibition is our tribute to that great comedian, Miguel Gila. To that “other way” he had of doing things, to leaving a completely new mark on the world.

Pioneer, groundbreaker, genius: this small format exhibition is our tribute to that great comedian, Miguel Gila. To that “other way” he had of doing things, to leaving a completely new mark on the world.

Espacio Efemérides (Ephemeris Space) reinvents itself again with this latest small format show. This is a platform for the dissemination of technological heritage and Telefónica’s archives, a collection of great value consisting of objects, documents and audiovisual material that is essential if one is to understand communications in the 20th century, offering key information on the social context of the past 120 years.

This exhibition is a tribute to that “other way” of doing things, leaving a completely new mark on the world. It is not exactly an exhibition of the great Gila’s life, nor does it seek to be a comprehensive recap of his performances, his travels and his relationships. We wanted to focus on his colossal body of work and how he broke new ground in the various professional fields in which he was involved. Gila was able to leave his mark on everything he did.

Gila – a new kind of humour

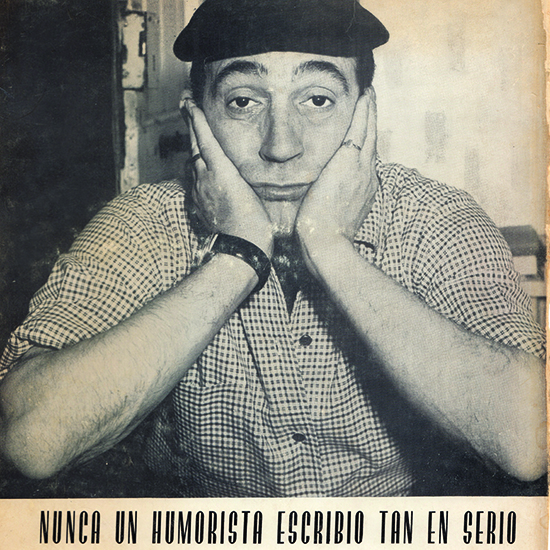

Miguel Gila Cuesta (Madrid, 1919 – Barcelona, 2001) was, among other things, a comedian, actor and cartoonist. Of humble origin, he would recall how he never had any access to culture as a child, giving him a lifelong voracious appetite for knowledge, learning and reading, as was evident in his decision to enrol in the Faculty of Philosophy and Literature at the University of Buenos Aires at the age of fifty.

Perhaps as a result of his life experiences, Gila knew how to transform the sad realities that he had seen into an absurd fit of laughter, retelling his life just as he wanted to tell it. As Gila said, you have to “cry a little and laugh a lot”.

Before acting on the stages that made him famous, Gila was best known for his radio performances. Radio was the genesis of his often critical comedy shows, such as Vieja Chismosa (“Old Gossip”) or those for children, such as Radio Cocoliche. He also commentated on football matches for the radio and reviewed the theatre productions which came to Zamora, the city in which his media career began, as well as hosting dedication shows in which he played records that hardly anyone remembers these days.

His comedy programmes were a great success – this was a new kind of humour and the public applauded. Gila started to dream of new horizons.

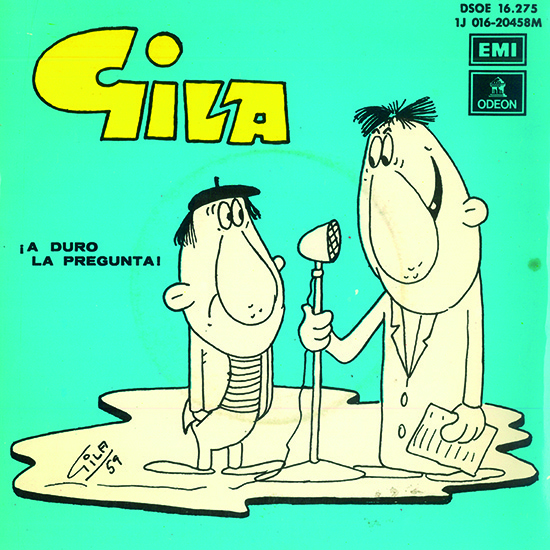

Graphic humour

To a certain extent, the importance of Gila’s graphic work has been eclipsed by his enormous popularity as a monologist. Nevertheless, it represents another of his major contributions to the history of comedy. As he recalled, graphic humour was what he liked the most.

Since childhood he had shown real artistic ability. He filled the most unlikely places with his drawings. His skill led him to study drawing at the School of Arts and Crafts, encouraged by his grandfather and his uncle.

In 1940, he published his first cartoon in a the magazine Domingo, followed by Imperio, Flechas y Pelayos and the weekly Cucú. However, his great opportunity came with his work for La Codorniz, a weekly satirical magazine that was very well-known at the time and which proved to be the vehicle through which he began to gain recognition. He later had his work published in another renowned magazine, Hermano Lobo. During his time in the Americas he founded La Gallina, as well as Don José in Spain, along with other well-know humourists.

His cartoons of characters with big noses combined with a critical humour, with messages that were sometimes subtle, sometimes brutal and direct, in which the surprise hits you in the form of a corrosive humour, full of protest. His inspiration came, he said, from the the things he saw from day to day in the street: children, donkeys, women wearing hats, women not wearing hats, elderly people, beggars…

I hope that’s the the only time you’re born alone

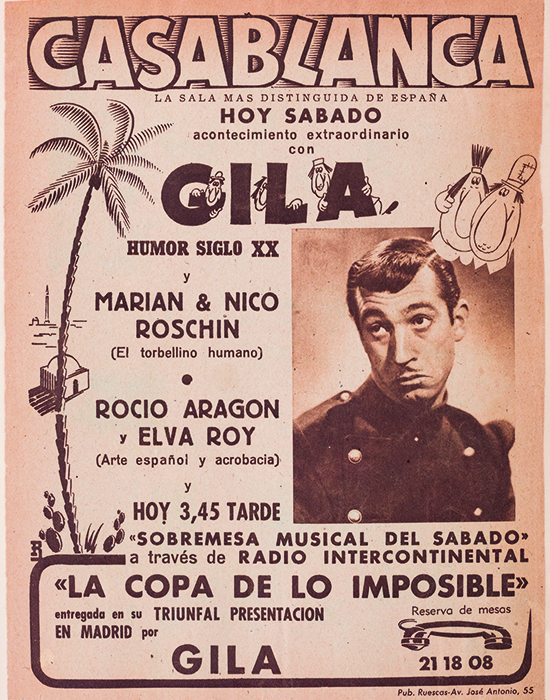

Gila’s best-known comedy activity, the one which his vast public identify him with, are his monologues. These were absurd stories which Gila referred to as simply “talking about things”. All those who listened to them would laugh till they ached at the observations of this man who would sometimes be dressed as a soldier, sometimes wearing a beret but almost always in a red shirt, accompanied by his inseparable companion: a telephone. These monologues were a groundbreaking development in comedy.

According to Gila, the spark for his performances could be found in the routines he improvised for his younger brothers. The first time he went on stage was in 1950, at a show organised by Radio Zamora. Seeing the success he had had, he began to think that this might be the future he was looking for.

One year later, having scrimped and saved, Gila performed in Madrid. There are various accounts of his debut, although we know for certain that it was at the Fontalba Theatre in 1951 and that Gila, in a soldier’s uniform, emerged on the stage from the prompt box below, asking if this was the exit for Goya metro station. Although he was a resounding success, he had to wait for his second chance, an improvised performance at the Pavillón banquet hall, in order to get the contract he dreamt of and the the definitive take-off of his stage career.

His first repertoire consisted of three monologues: the war, one in which he recounted his experiences as a gangster in Chicago in Al Capone’s mob and the most innovative and surreal of all, the story of his life: “When I was born, my mother wasn’t around”. This was the start of a new and very different type of comedy.

The logic of the absurd

Pioneer, groundbreaker, genius. Many adjectives have been used to describe Gila and his style of humour. His monologues always have the capacity to surprise, with the audience reacting with incredulity, wonderment and lots of laughter.

“You killed my son, although I had to laugh…” or “When I was born, my mother wasn’t around”. He made the preposterous seem normal, the humour of the absurd. However, as he himself said, this absurdity had a certain logic, he had to make the madness credible – the only limit he put on himself when writing.

A new kind of humour had been born which oscillated between the limits of reality and the absurd. Nevertheless, his monologues were also critical. They denounced poverty, inequality, cruelty to animals and, of course, they railed against war. War was depicted as preposterous, ridiculous. As Gila said: “I’m opening fire on war”, against those that sought to wage it, “armed only with irony and mockery”, reflecting its senselessness.

The telephone, his great discovery

Despite what we might believe, Gila did not always perform his monologues with a telephone by his side. At first he acted alone, standing in front of a microphone. Nevertheless he recognised that he felt uncomfortable standing so still as he performed. He had a few well-known comic partners such as Tony Leblanc and Mary Santpere, and yet they didn’t completely convince him. Gila really saw himself acting alone, as he knew how complicated working with a partner could be. However, he also needed a “somebody” who would reply to him to break the almost priestly pose he disliked so much.

After agonising on the matter for some time, he finally hit upon the solution of a telephone, a silent companion that allowed him to enrich and nuance his monologues. Using this idea of the phone calls, Gila not only rewrote the sketches that he already had in his repertoire, but also created many others by “simply” dialling a number and embarking on a conversation that might lead to an absurd situation that was guaranteed to provoke his audience’s mirth. As well as simulating a conversation, it gave him the time to think about what to do while his public laughed. Gila pretended to listen attentively to what he was hearing on the other end of the line.

Having revolutionised comedy with his absurd monologues, Gila now gave a fresh turn of the screw, breaking new ground with this peculiar new stage partner. As Gila recognised in his memoirs, the telephone was his greatest discovery.

More than just monologues

It should come as no surprise that Gila was also a writer. It’s logical, given that he wrote his own monologues. However, it went further than that. Gila wrote plays including Tengo Momia Formal (“I Have a Formal Mummy”), Abierto por Defunción (“Open Due to Bereavement”), Yo Encogí la Libertad (“I Shrank Freedom”) and many others that were staged by both his own theatre company and by others.

There was also the side to him which we might call “serious Gila”. His play La Pirueta (“The Pirouette”), co-written with his wife Dolores Cabo and which premiered in Barcelona, left a deep impression on the public as it was an uneasy, dispiriting work, far removed from his usual absurd humour.

Neither should we forget Gila the poet. About a year before he died, Gila announced his intention to publish his poems which he had written throughout his life and yet were rarely seen. This project, which was to be entitled Chapuzas (“Botch Jobs”), unfortunately never materialised.

Gila in advertising

It is obviously easy to identify Gila the actor through his monologues. He made 35 films, either as one of the stars or as a crowd-pulling supporting actor.

However, another of his major contributions was to the world of advertising. He advertised Profidén toothpaste and starred in a series of advertisements for the razor blade manufacturer Filomatic.

Luis Bassat, the company’s advertising director suggested that he appear in a television campaign they had planned. Gila was an active participant, suggesting a number of ideas which were considered groundbreaking at the time. Bassat himself said that Gila taught him the meaning of advertising creativity. It was Gila’s idea to make a series of different adverts in order to keep the public’s attention, as well as to finish each of them with a catchphrase they would remember. The campaign was a huge success, with Gila’s ads a determining factor in the brands popularity.

Another groundbreaking moment for advertising was the TV campaign for Agni, a domestic appliance manufacturer. In these adverts, Gila would draw one of his famous cartoons, once again adding a catchphrase that was to become famous: “The moral of this story? Buy an Agni and throw the old one out”.

*Sources:

- https://www.miguelgila.com/blog/biografia/2019-centenario-del-nacimiento-de-miguel-gila/

- Chumy Chúmez: ‘Miguel Gila is the greatest cartoonist that Spain has produced since the Civil War’

- José Luis Coll: ‘Gila is the loudest belly laugh of the 20th century’